|

|

||||||||||||||||

The New World Order cannot be understood without accounting for the role of

religion and religious organizations. During the Cold War, not much attention

was paid to the phenomenon of nationalism and religion. Marxists, Liberals,

nation-builders and integration specialists treated it as a marginal variable.

In the Western political systems a frontier has been drawn between man's inner

life and his public actions, between religion and politics. The West is characterized

by a desecularisation of politics and a depolitisation of religion. Part of

the elite Western opinion views religion as irrational and premodern; "a

throw-back to the dark centuries before the Enlightenment taught the virtues

of rationality and decency, and bent human energies to constructive, rather

than destructive purposes" (Weigel, 1991: 27) In the Communist block, religion

was officially stigmatized as the opium of the people and repressed. In theories

of integration and modernization, secularization was considered a 'sine qua

non' for progress. Consequently, the explosion of nationalist and ethnic conflicts

was a great surprise.

What about religious conflicts? Are we in for surprises too? The answer is:

yes probably. As late as August 1978, a US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

Paper asserted confidently that "Iran is not in a revolutionary or even

a pre-Revolutionary situation." Roger Williamson (1990) considers this

the most glaring example of Western incomprehension and misconception of Modern

Islam. The fundamental mistake of Western observers, he argues, is the assumption

that since Christianity plays little direct role in shaping policy in Western

nations, the separation of religion and political decision-making can be assumed

in the Middle East as well. Since the fall of the Shah, research about the role

of religions in conflict dynamics has increased. The amount of research, however,

lags considerable behind the boom of studies of ethnic and nationalistic conflicts.

The attention for the role of religion in conflicts has been stimulated by positive

and negative developments, including the desecularisation of the World and the

rise of religious conflicts. In most Strategic Surveys, attention is now paid

to the militant forms of religious fundamentalism as a threat to peace. Also

important has been the phenomenon of realignment or the cross denominational

cooperation between the progressives and traditionalists with respect to certain

specific issues (Hunter, 1991). Illustrative is the view of the Catholic Church

and the Islam Fundamentalists vis à vis the Report by the United Nations

Population Fund on population growth.

Attention has also been drawn by the increased engagement of churches or church

communities in the search for détente or constructive management of conflicts.

Think of the voice of the American bishops in the nuclear debate in the eighties;

the role of churches in the democratic emancipation of Central and Eastern Europe;

or the impact of church leaders on the conflict dynamics in several African

conflicts. All have attracted considerable attention. Not only in South Africa

with Desmond Tutu or Allan Boesak, but also, for example, in Sudan (Assefa,

1990; Badal, 1990), Mozambique and Zaire. Mgr. Jaime Gonçalves, the archbisop

of Beira played an important role in the realization of a peace-agreement in

Mozambique on 4 October 1992. It ended a gory war in which a million lives were

wasted and half of the population were on the run for safety. In Zaire, Monseigneur

Laurent Monsengwo was elected as chairman of the "High Council of the Republic",

and played a central role in the difficult negotiations between President Mobutu

and his opponents. The Burundian catholic bishops, representing half of the

population, are now mediating towards the development of a more collegial government

to prevent further violence. Finally, we should also mention the role of the

church in empowering people in the Third World with the Liberation theology

and many recent efforts to provide peace services in conflicts areas, including

field-diplomacy.

To get a better grasp of what religions or religious organizations could do,

to help to promote a constructive conflict dynamic, one could start by investigating

systematically which positive or negative roles they play now. Consequently,

suggestions would be made about how to reduce the negative and strengthen the

positive impact. Religious organizations can act as conflicting parties, as

bystanders, as peace-makers and peace builders (see Table 1).

Table 1. Religious organizations in conflict dynamics

|

RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN

CONFLICT DYNAMICS:

|

|

CONFLICTING PARTIES

|

|

Religious wars

Low-intensity violence Structural violence Cultural violence |

|

BYSTANDERS

|

|

PEACE-BUILDERS AND PEACE-MAKERS

|

|

Peace-building

|

|

Empowering people

Influencing the moral-political climate Development cooperation-humanitarian aid |

|

Peace-making

|

|

Traditional diplomatic efforts

Track II peace-making Field-diplomacy |

Since the awakening of religion, wars have been fought in the name of different

gods and goddesses. Still today most violent conflicts contain religious elements

linked up with ethno-national, inter-state, economic, territorial, cultural

and other issues. Threatening the meaning of life, conflicts based on religion

tend to become dogged, tenacious and brutal types of wars. When conflicts are

couched in religious terms, they become transformed in value conflicts. Unlike

other issues, such as resource conflicts which can be resolved by pragmatic

and distributive means, value conflicts have a tendency to become mutually conclusive

or zero-sum issues. They entail strong judgments of what is right and wrong,

and parties believe that there cannot be a common ground to resolve their differences.

"Since the North-South conflicts in the Sudan have been cast in religious

terms, they developed the semblance of deep value conflicts which appear unresolvable

except by force or separation" (Assefa, 1990). Religious conviction is,

as it has ever been, a source of conflict within and between communities. It

should, however, be remembered that it was not religion that has made the twentieth

the most bloody century. Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao Tse-tung, Pol Pot and their

apprentices in Rwanda maimed and murdered millions of people on a unprecedented

scale, in the name of a policy which rejected religious or other transcendent

reference points for judging its purposes and practices (Weigel, 1991: 39).

Those policies were based on an ideology having the same characteristics as

a religion.

In a world where many governments and international organizations are suffering

from a legitimacy deficit, one can expect a growing impact of religious discourses

on international politics. Religion is a major source of soft power. It will,

to a greater extent, be used or misused by religions and governmental organizations

to pursue their interests. It is therefore important to develop a more profound

understanding of the basic assumption underlying the different religions and

the ways in which people adhering to them see their interests. It would also

be very useful to identify elements of communality between the major religions.

The major challenge of religious organizations remains to end existing and prevent

new religious conflicts. In December 1992, 24 wars were counted with a religious

background (adjusted AKUF-Kriege-Datenbank). Most of them were situated in Northern

Africa, the Middle East, the ex-USSR and Asia. In Europe there were only two:

Yugoslavia and Northern Ireland. No religious wars were registered in the Americas

(See Table 2).

These wars could be further classified by distinguishing violent conflicts within

and between religions and between religious organizations and the central government.

In Europe, Bosnian Muslims have, for more than two years, been brutally harried

by Serbs who are called Christians. On the border between Europe and Asia, Christian

Armenians have thumped Muslim Azzeris, and Muslims and Jews still shoot each

other in Palestine.

WARS WITH A RELIGIOUS DIMENSION

1. Mayanamar/Burma 1948 Buddhists vs. Christians

2. Israel/Palestinian 1968 Jews vs. Arabs )Muslims-Christians)

3. Northern Ireland 1969 Catholic vs. Protestants

4. Philippines (Mindanao) 1970 Muslims vs. Christians (Catholics)

5. Bangladesh 1973 Buddhists vs. Christians

6. Lebanon 1975 Shiites supported by Syria (Amal) vs. Shiites supported by Iran

(Hezbollah)

7. Ethiopia (Oromo) 1976 Muslims vs. Central government

8. India (Punjab) 1982 Sikhs vs. Central government

9. SudanWITH 1983 Muslims vs. Native religions

10. Mali-Tuareg Nomads 1990 Muslims vs. Central government

11. Azerbejdan 1990 Muslims vs. Christian Armenians

12. India (Kasjmir) 1990 Muslims vs. Central government (Hindu)

13. Indonesia (Aceh) 1990 Muslims vs. Central government (Muslim)

14. Iraq 1991 Sunnites vs. Shiites

15. Yugoslavia (Croatia) 1991 Serbian orthodox Christians vs. Roman Catholic

Christians

16. Yugoslavia (Bosnia) 1991 Orthodox Christians vs. Catholics vs. Muslims

17. Afghanistan 1992 Fundamentalist Muslims vs. Moderate Muslims

18. Tadzhikistan 1992 Muslims vs. Orthodox Christians

19. Egypt 1977 Muslims vs. Central government (Muslim) Muslims vs. Coptic Christians

20. Tunesia 1978 Muslims vs. Central government (Muslim)

21. Algeria 1988 Muslims vs. Central government

22. Uzbekisgtan 1989 Sunite Uzbeks vs. Shiite Meschetes

23. India (Uthar- Pradesh) 1992 Hindus vs. Muslims

24. Sri Lanka 1983 Hindus vs. Muslims

Table 2: Wars with a Religious Dimension

<<Object>>

Source: Gantzel et al., (1993)

Further east, Muslims complain of the Indian army's brutality towards them

in Kashmir, and of Indian Hindu's destruction of the Ayodhya mosque in 1992.

Islam, as Samuel Huntington has put it, has bloody borders (Huntington, 1993).

It was Huntington who recently provided the intellectual framework to pay more

attention to the coming clash of civilizations. Civilizations are differentiated

from each other by history, language, culture, tradition and, most importantly,

religion.

He expects more conflicts along the cultural-religious fault lines because (1)

those differences have always generated the most prolonged and the most violent

conflicts; (2) because the world is becoming a smaller place, and the increasing

interactions will intensify the civilization- consciousness of the people which

in turn invigorates differences and animosities stretching or thought to stretch

back deep in history; (3) because of the weakening of the nation-state as a

source of identity and the desecularisation of the world with the revival of

religion as basis of identity and commitment that transcends national boundaries

and unites civilizations; (4) because of the dual role of the West. On the one

hand, the West is at the peak of its power. At the same time, it is confronted

with an increasing desire by elites in other parts of the world to shape the

world in non-Western ways; (5) because cultural characteristics and differences

are less mutable and hence less easily compromised and resolved than political

and economic ones; (6) finally, because increasing economic regionalism will

reinforce civilization-consciousness.

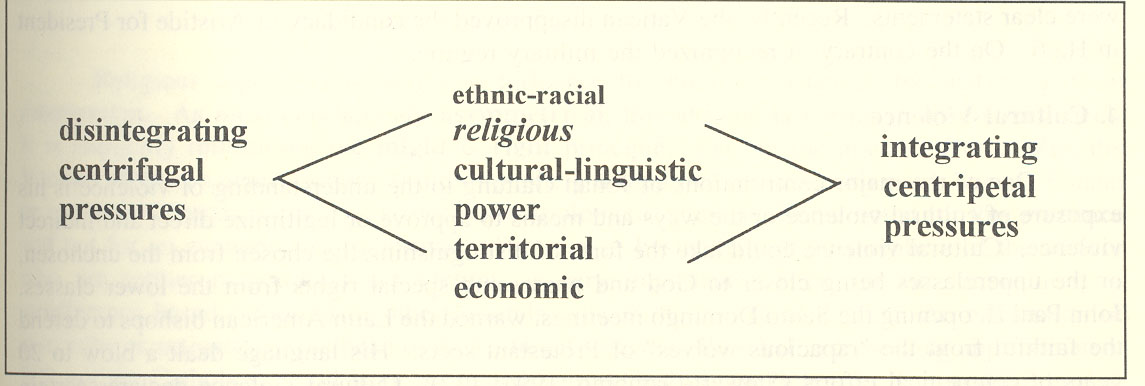

Of course there are no ' pure ' religious conflicts. It is the correlation with

other integrating or disintegrating pressures which will determine the dynamics

of a conflict. There is a need for a more sophisticated typology.

For each conflict in which religion is involved, a cross-impact analysis is

necessary of at least six variables which together could reinforce a constructive

or a destructive conflict dynamic (See the Figure 1).

<<object>>

To further their interests religious organizations make also use of low-scale

violence, political repression and terrorism. Salmon Rushdie or Taslima Nasrin

in Bangladesh were forced into hiding from Muslim fundamentalists who want to

punish them with death. Each religion has its fanatic religious fundamentalists.

The Kach Party, which was leaded by Rabbi Meir Kahane until his death in November

1990, used tactics of abusing and physically attacking Palestinians. Kahane

believed in a perpetual war and preached intolerance against the Arabs. Christian

fundamentalists in the US cater a "Manifest Theology", a fundamentally

Manichean worldview in which "we" are right, and all civil and aggressive

intentions are projected to "them" (Galtung, 1987).

"Because 'they' are evil and aggressive forces of chaos in the world, 'we'

then have to be strongly armed, but do not perceive ourselves as aggressive

even when attacking other countries" (Williamson, 1992: 11). Intolerance

is also spawn by a minority of Islamic organizations, like Egypt's Gama'at al-Islamiya,

Libanon's Hezbullah or Algeria's Islamic fundamentalists. All pursue a policy

of violent confrontation, based on the convention that armed struggle or 'jihad'

is a necessary and appropriate response to the enemies of God, despotic rulers

and their Western allies.

Several religious organizations also support structural violence by endorsing a centralized and authoritarian decision-making structure and the repression of egalitarian forces. Churches have sympathized with authoritarian government. The concord of the Vatican with Portugal in 1940, the agreement with Franco in 1941, and the support of authoritarian regimes in Latin-America were clear statements. Recently, the Vatican disapproved the candidacy of Aristide for President in Haiti. On the contrary, it recognized the military regime.

One of the major contributions of Johan Galtung to the understanding of violence

is his exposure of cultural violence or the ways and means to approve or legitimize

direct and indirect violence. Cultural violence could take the form of distinguishing

the chosen from the unchosen, or the upper-classes being closer to God and possessing

special rights from the lower classes. John Paul II, opening the Santo Domingo

meetings, warned the Latin American bishops to defend the faithful from the

"rapacious wolves" of Protestant sects. His language dealt a blow

to 20 years of ecumenical efforts (Stewart-Gambino, 1994: 132). Cultural violence

declares certain wars as just and others as unjust, as holy or unholy wars.

The peace price given to Radovan Karapi¦, the Serbian leader in Bosnia,

by the Greek Orthodox Church, for his contribution to world peace could easily

be labeled as cultural violence. In July 1994, Kurt Waldheim was awarded a papal

knighthood of the Ordine Piano for safeguarding human rights when he served

with the United Nations. His services in the Balkans for the Nazis were seemingly

forgiven. Both were made religious role models.

It is clear that the causes of religious wars and other religion related violence

have not disappeared from the face of the earth. Some expect an increase of

it. Efforts to make the world safe from religious conflicts should then also

be high on the agenda. Religious actors should abstain from any cultural and

structural violence within their respective organizations and handle inter-religious

or denominational conflict in a non-violent and constructive way. This would

imply several practical steps, such as a verifiable agreement not to use or

threaten with violence to settle religious disputes. It must be possible to

evaluate religious organizations objectively with respect to their use of physical,

structural or cultural violence. A yearly overall report could be published.

Another step would be furthering the 'depolitisation' of religion. Power also

corrupts religious organizations. In addition, depolitisation of religion is

a major precondition for the political integration of communities with different

religions.

Very important is the creation of an environment where a genuine debate is possible.

Extremist rhetoric flourishes best in an environment not conductive to rational

deliberation. Needless to say, extremist rhetoric is very difficult to maintain

in a discursive environment in which positions taken or accusations made can

be challenged directly by rebuttal, counter propositions, cross-examinations

and the presentation of evidence. Without a change in the environments of public

discourses within and between religious organizations, demagogy and rhetorical

intolerance will prevail. In his latest book Projekt Weltethik, Hans Küng

rightly concludes that world peace is impossible without religious peace, and

that the latter requires religious dialogue.

Religious organizations can also influence the conflict dynamics by abstaining from intervention. As most conflicts are 'asymmetrical', this attitude is partial in its consequences. It is implicitly reinforcing the 'might is right' principle. During the Second World War, the Vatican adopted a neutral stand. It didn't publicly disapprove of the German atrocities in Poland or in the concentration camps. To secure its diplomatic interests, Rome opted for this prudence and not for an evangelical disapproval. The role of bystanders, those members of the society who are neither perpetrators nor victims, is very important. Their support, opposition, or indifference based on moral or other grounds, shapes the course of events. An expression of sympathy or antipathy of the head of the Citta del Vaticano, Pius XII, representing approximately 500 million Catholics, could have prevented a great deal of the violence. The mobilization of the internal and external bystanders, in the face of the mistreatment of individuals or communities, is a major challenge to religious organizations. To realize this, children and adults, in the long run, must develop certain personal characteristics such as a pro-social value orientation and empathy. Religious organizations have a major responsibility in creating a worldview in which individual needs would not be met at the expense of others and genuine conflicts would not be resolved through aggression (Fein, 1992).

Religious organizations are a rich source of peace services. They can function

as a powerful warrant for social tolerance, for democratic pluralism, and for

constructive conflict-management. They are peace-builders and peace-makers.

Religions contribute to peace-building by empowering the weak, by influencing the moral-political climate, by developing cooperation and providing humanitarian aid.

(1) Empowering people

In the last quarter of this century, religious actors have been a major force

for social justice in the Third World and a movement for peace in the industrial

countries in the North.

People can be empowered by offering support to protest movements, for instance,

the God against the bomb action in North America and Europe. In both East and

West, churches issued a declaration in the 1980's supporting the goals of the

peace movement. The ecumenical peace engagement was particularly important in

creating a mass constituency for peace. The pastoral letter 'The Challenge of

Peace is God's Promise and our Response', issued in May 1983, challenged the

very foundation of U.S. nuclear policy and opposed key elements of the Reagan

administration's military buildup (Cartwight, 1993).

People can also be empowered by providing them with theological support against

injustice. In the Third World, many varieties of theology have been developed

which are critical of structural violence. The best known are the Liberation

theology in Latin America and the black theology in South Africa. These theologies

speak for putting an end to suffering caused by physical, structural, psychological

and cultural violence. The existence of a Christianity of the poor is a powerful

social force, confronted with repression and exploitation. Hundreds of church

workers, catechists, priests and bishops have undergone death threats, have

been tortured or murdered while working on the abolishment of poverty and injustice

(Lernoux 1982).

A wide varieties of initiatives were recently taken for protecting people from

violence. Examples are the 'Peaceworkers' who went into conflict areas to accompany

people whose lives were in danger. In one case, from the Philippines, 25 volunteers

came on short notice to be with 650 refugees in a church surrounded by death

squads threatening to kill the refugees. The presence of the international group,

which was holding a press conference, prevented a potential massacre (M.E.Jeger,

1993). Another example are the activities of the 'Cry for Justice' organizations

which were, according to Father Nangle, a response to a call from Haiti "for

as many internationals as possible for as long as possible to go into the most

violent places in Haiti's countryside to be a protective presence, to protect

human rights abuses, and to foster a climate for free and open dialogue and

assembly".

(2) Influencing the moral-political climate

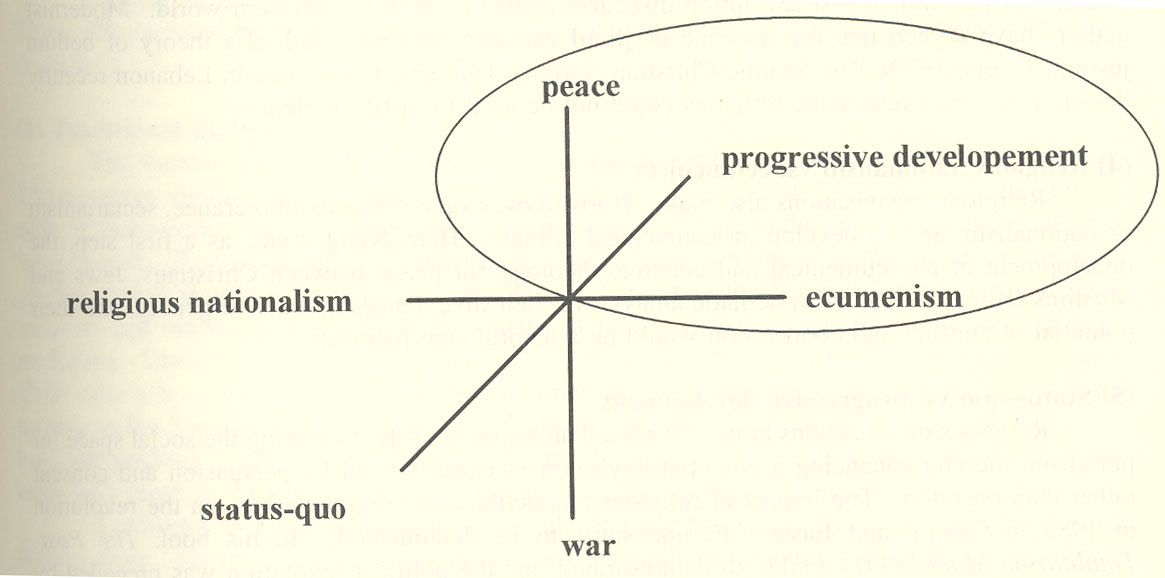

The major variable, which religious organizations can influence, is the moral-political climate. The moral-political climate at the international or domestic level can be defined in terms of the perceived moral-political qualities of the environment in which the conflicting parties operate. Some climates tend to be destructive, but others enhance conditions for constructive conflict-management. Religious organizations influence the moral-political climate by justifying war or peace, tolerance or intolerance, conservatism or progressivism (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dimensions of the moral-political climate

(3) War vs. Peace

With respect to war and peace, the religious approaches could be divided under

two main categories: pacifism and just war doctrine (Life and Peace Report,

1990). Many varieties of pacifism could be distinguished: optimistic, mainstream

and pessimistic (Ceadel, 1987). For some, it means an unconditional rejection

of participation in armed struggle; for others, it refers to an active engagement

in peace-making. The Quakers traditionally have devoted themselves to the dismantling

of enemy-images and reconciliation. With Gandhi as a source of inspiration,

others have developed non-violent peace-making strategies.

Christianity is contributing to arms control and to non-violent conflict resolution,

through the evolution of the just war tradition and the acceptance of it as

its mainstream normative framework for reflecting on problems of war and peace.

The 'ius ad bellum' principles (which determine when resort to armed force is

morally justified) and the 'ius in bello' principles (which determine what conduct

within war is morally acceptable) have significantly influenced current international

law. Some analysts consider the liberation theology as a recent but radical

variant of this doctrine, even though certain liberation theologians tend to

be advocates of non-violence and some are considering it necessary to develop

just revolution principles. In Latin-America, some theologians of liberation

pondered on the use of 'revolutionary' violence, and in South Africa, revolutionary

'second violence' was endorsed against the 'first violence' of the Apartheid

system. A just war or just revolution discourse is also alive in the Muslem

world. Modernist authors have argued that the doctrine of 'jihad' can also be

considered as a theory of bellum justum (Peters, 1979). The Islamic-Christian

National Dialogue Committee in Lebanon recently declared that their respective

religions could not be used to justify violence.

(4) Religious Nationalism vs. Ecumenism

Religious organisations also make efforts to overcome religious-intolerance, sectarianism or nationalism, and to develop an ecumenical climate. Hans Küng urges, as a first step, the development of an ecumenical and concrete theology for peace between Christians, Jews and Muslims (Küng, 1990). A systematic analysis of their divergences and convergences, and their potential of conflict and cooperation would be a helpful step forwards.

(5) Status-quo vs. Progressive Development

Religious organisations have also played an important role in clearing the social

space for pluralism, thereby enhancing a potential environment characterized

by persuasion and consent rather than coercion. The impact of religious conviction

and religious actors on the revolution in 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe

starts to be documented. In his book The Post-Totalitarian Mind (1991), Goldfarb

demonstrated that the political revolution was preceded by a moral and cultural

revolution. Garton Ash refers, for example, to the impact of John Paul II on

his homeland Poland in March 1979. "For nine days the state virtually ceased

to exist, except as a censor doctoring the television coverage. Everyone saw

that Poland was not a communist state. John Paul II left thousands of human

beings with a new self-respect and renewed faith, a nation with rekindled pride,

and a society with a new consciousness of its essential unity" (Ash, 1985).

Religious organisations also played a crucial role in the peaceful revolution

in South Africa. There is the steadfastness of the condemnation of violence

by black religious leaders. Of great significance was also the role of the Dutch

reformed Church which distanced itself from Apartheid and condemned it as biblically

unwarranted. This helped to deprive the racial radicals of the moral legitimacy

of violence.

(6) Development, Cooperation, and Humanitarian Aid

A great number of INGO's, engaged in all kinds of development projects, have a religious base. I do not know of any study assessing the efforts of religious INGO's, but scattered data suggest that these efforts are considerable. In 1974 Belgium had 6,283 catholic missionaries in the world. In 1992 this number decreased to 2,766: 1,664 in Africa, 633 in America, 464 in Asia, and 5 in Oceania. In the same year Caritas Catholica Belgium spent 145 million BF on emergency aid, 290 million BF on food aid, 22 million BF in Yugoslavia, 17 million BF on micro-projects in other parts of the world, and 21 million BF to help refugees and migrants in Belgium.

Several religious organisations distinguish themselves through peace-making efforts. Those efforts could be of a traditional diplomatic nature or be categorized as Track II or Field diplomacy.

(1) Traditional diplomatic efforts

The Vatican has been involved in several cases as a mediator. Its Secretariat

of State has 150 members divided over eight language desks. It is represented

in 122 countries. Its highest ranking ambassador is called a 'nuncio' who represents

the Pope to the Heads of state and to the local church. They gain much information

of local affairs from the 150,000 parish priests who preside over 800 million

Catholics worldwide. To the extent the Vatican lacks traditional state interests

and maintains a sense of 'objectivity', it makes it a good candidate for international

mediation. During 1978-1984 Pope John Paul II mediated successfully between

Argentina and Chile over a few islands at the tip of South America. Both countries

narrowly averted war by turning to the Vatican as a mediator. The Vatican was

succesful only in keeping the parties at bay, not pushing a settlement. In the

end, that proved quite enough once domestic factors, especially those in Argentina

after the Maledives/Falklands war, changed.

According to Thomas Princen (1992), the Papacy has special resources that few

world leaders share. Six resources, which appear to be common to other international

actors, stand out.

(a) Moral legitimacy: The Pope has a legitimate stake in issues such as peace-making

or human rights having a spiritual or moral component. During the Beagle Channel

mediation, the Pope appealed to the moral duty to do all necessary to achieve

peace between the two countries.

(b) Neutrality: In the dispute mentioned above, there was no question that the

Vatican had no interests in the disputed islands.

(c) Ability to advance other's political standing: A papal audience, a papal visit or involvement confers political advantage on state leaders. This advantage can be used at key junctures in a mediation: gaining access; deciding on agenda and other procedures; delivering proposals. The demarches done by the president of the United States, Jimmy Carter, to resolve the issue peacefully were distrusted by the two military governments who found his stand on human rights annoying (Princen, 1992).

(d) Ability to reach the (world) public opinion: The Pope can command the attention of the media. This is especially true for the perigrinating John Paul II.

(e) Network of information and contacts: The information and communication network of the Catholic Church is extensive. For a localized dispute, communication channels outside conventional diplomatic channels can be significant.

(f) Secrecy: Confidentiality is a major asset for mediation. As an organisation with no claim to democratic procedures or open government, the Holy See is known to be able to keep a secret. Maintaining confidentiality is a standard operating procedure in the Vatican.

Thomas Princen concludes his analysis of the mediation by the Vatican by observing that when pay-offs are not the primary obstacle, when the interaction between disputes is inadequate, when face-to-face talks and face-savings devices are in short supply, a powerless transnational actor can influence disputants in subtle ways. He also notices that the mediation effort in the dispute mentioned above turned out to be a terrible headache for the mediation team and the Pope. What started out as a six-month enterprise turned out to be a six-year ordeal. He further observes that, on the whole, however, the Vatican remains a re-active player, for whom power politics continues the dominant paradigm.

(2) Track II Peace-making

The peace-making activities of NGO's, be it of a religious or non-religious nature, are getting more attention. A great deal of research is, however, needed to have insight in the potential of the rich amount and variety of peace services.

Traditionally, a lot of peace work has been delivered by the Quakers. Various efforts have been directed toward conciliation to stop "all outward wars, strife and fighting." Under the heading "conciliation" come especially efforts to promote better communication and understanding by bringing people together in seminars and efforts to work with the conflicting parties. Adam Curle and Kenneth Blulding are the two most well-known academic spokesmen of this approach. The definition given by Adam Curle for conciliation describes the Quakers assumptions: "Activity aimed at bringing about an alteration of perception (the other is not so bad as we imagined; we have misinterpreted their actions, etc.) that will lead to an alteration of attitude and eventually to an alteration of behavior" (Yarrow, 1977).

This kind of conciliation is the most appropriate if conflicts primarily arise over a different definition of the situation. For other conflicts related to gross injustices or unequal power, the Quakers use methods of witness or advocacy. Essential for effective conciliation is the establishment of confidence, impartiality and independence. Yarrow describes the kind of impartiality, which tends to promote 'balanced partiality,' that is, listening sympathetically to each side, trying to put themselves in the others party's place. Another characteristic of balanced partiality is the Quakers concern for all people involved in a situation. The Quakers teams--Quakers have tended to entrust mediatory work to at least two friends--emphasize the need to maximise the gains that might accrue to both sides through a settlement. Also, several other religious organisations are increasingly engaged in peace-making efforts. An important role was played by the Catholic community of San Egidio in Rome to reach a Peace Agreement in Mozambique in October 1992 (Sauer, 1993).

Non-governmental peace-makers tend to approach conflicts from a different perspective shared by the traditional diplomacy. The new approach, carrying different names such as Track II, parallel, multi-track, supplemental, unofficial, citizen diplomacy, or 'interactive problem-solving diplomacy' reflect a new conflict resolution culture. This new conflict resolution culture differs from the traditional one with respect to four points.

(a) Goals: The nongovernmental diplomats tend to make a distinction between conflict settlement (by authoritarian and legal processes) and conflict-resolution (by alternative dispute resolution skills). Conflict-resolution aims at an outcome that is self-supporting and stable because it transforms the problem to long-term satisfaction of all the parties (Burton, 1984).

(b) Attitude vis-à-vis the conflicting parties: Track II diplomacy assumes that the motivations and intentions of the opposing sides are benign; this contrasts strongly with the conflict culture of the traditional diplomacy in which distrust and a more negative perception of men prevails. Track II peace-makers further believe that only the conflicting parties can arrive at a solution; in other words, their task consists mainly of facilitating the process. They also try to help understanding of so-called 'irrational behavior' that is disapproved by dominant social norms. From the point of view of the decision-maker, it could be perceived as the best they would do given what they know about the intentions of the other parties and the perceived options. They believe that not only the government, but different layers of the respective society should have a say in the peace-making process. A stable peace ought to be embedded in a democratic environment.

(c) Towards a multi-level and comprehensive approach: Track II peace-makers see their efforts as complementary to the official diplomatic efforts. They believe that peace has to be a multi-level effort and that governmental as well as non-governmental actors should be involved. The latter could be private persons or organisations, and national or transnational institutions of a secular or religious nature. They also believe that a sustainable peace requires a comprehensive approach in which the necessary diplomatic, political, military, economic, cultural and psychological conditions are created.

(d) Peace, a learning process: Track II peace-makers assume that, in many cases, violence and war are the consequence of a wrong assessment of the consequences of war or of a lack of know-how to manage conflicts in a more constructive way. They also believe that warlike or peaceful behavior is learned behavior, and that what is learned could be unlearned through peace-research and peace-education.

Track II diplomacy involves a series of activities such as 1) the establishment of channels of communication between the main protagonists to facilitate exploratory discussions in private, without commitment, in all matters that have or could cause tensions; 2) setting up an organization which can offer problem-solving services for parties engaged in conflicts within and between nations; 3) the establishment of a center to educate people undertaking such work; and 4) the creation of a research center or network in which know-how and techniques are developed to support the above mentioned tasks.

(3) Field-diplomacy

Recently we notice, in several parts of the world, new initiatives for developing what could be called 'field-diplomacy'. This new creative energy has been jolted by three factors. First of all, there is the failure of the traditional diplomacy of governmental and intergovernmental organizations to prevent conflicts (Bauwens and Reychler, 1994).

Important also is the explosion of peace-keeping and humanitarian relief efforts. These efforts absorbing huge budgets do not solve conflicts, and could have been used in an earlier phase of the conflict to prevent violence escalation. Peace-keepers and humanitarians seem to be doomed to Sisyphus efforts, an endless pushing up of peace-building stones against the mountain of human suffering. When the task seems over, the stones role back and they can start again.

A third factor stimulating 'field-diplomacy' is the growing awareness that case studies and especially practical experience in the field would enhance the research work and the training of professional conflict-managers. As compared to other professions, such as lawyers, economists, or physicians who have respectively their law courts, business and patients or dead corpses to try out their theories, most peace-researchers have no practical experience. In addition, certain kinds of information to understand the dynamics of a conflict requires the analyst to be in the field.

The confluence of these factors started the development of a third generation of peace-making approaches: field-diplomacy. It refers to sending non-governmental teams to conflict areas, for an extended period, to stimulate and support local initiatives for conflict prevention. This means, in the first place, creating a network of persons based on trust. Such a network or trust bank is necessary for the observation of the conflict dynamics, for early warning, for an assessment of needs and for taking timely measures. Such measures could consist in keeping the communication channels between the conflicting parties open, creating a favorable climate for the explorations of solutions, developing a constructive conflict culture, keeping account of the total costs and benefits of the conflict, giving advice and evaluating official peace proposals or agreements. An effective contribution to conflict prevention requires a credible presence in the conflict area of professional volunteers who empathize with the concerns, needs and preferences of the communities in which they operate. To be effective they need to earn the respect and the trust of the local opinion-leaders. The organization, the personal and the methods for this kind of peace-making and peace-building are still in an embryonic state.

Among the pioneering organizations, we could mention, for example, 'Witness for Peace' who operated in Nicaragua, and the Swedish 'Peace Monitoring in South Africa' (PEMSA). Some organizations specialize in one task. The 'Peace Brigade International' takes care of the security of threatened activists. 'International Alert', an INGO situated in London, tries to improve conflict prevention by networking the humanitarian organizations, research institutes, peace movements, conflict resolution networks, human rights organizations and the media of each country, and by organizing training sessions in constructive conflict management.

An NGO with ample experience in constructive conflict management is 'Search for Common Ground' based in Washington (1993 Report). It began in 1982 and focused originally on Soviet-American relations. Now it works in the Russian Federation, the Middle East, South Africa, Macedonia and the United States. They develop what they call a common ground approach which draws from techniques of conflict resolution, negotiation, collaborative problem solving and facilitation. The aim is to discover not the lowest but the highest denominator.

In Belgium, a similar NGO called 'International Dialogue' will be created.

Recently at the American University of Beirut, a "Training for trainers

in conflict-resolution, human rights and peace democracy" was organized

by the International Peace Research Association (IPRA), International Alert

and UNESCO.

An initiative which could be referred to as a model for field-diplomacy is the

'Centre for Peace, Non-violence and Human Rights' in Osijek, Croatia, very close

to the Serbian border. The Peace Center was founded by a small group of people

in May 1991. They are 20 altogether, with a core group of five including Croats,

Serbs and Moslems. Under the Chairman Katarina Kruhonja, several initiatives

were undertaken to help and to protect people against threats. The members of

the Center practiced sitting in apartments with Serbs so that they could confront

the soldiers who came with orders to evict them. The members of the Center promote

human rights, teach methods and strategies of active non-violence, assist in

the resettlement of refugees, mediate in conflict situations, etc. The members

of the Center were frequently threatened and have been accused by the authorities

of being unpatriotic traitors. One of the heads of the local government said

that the Center would be destroyed and members would lose their jobs if they

would continue their activities.

Several organizations are addressing violence in their own countries. Mr.Upchurch

is focusing violence in Los Angeles where in 1,992,857 young men and women were

killed in group related violence. Not only at non-governmental but also at governmental

levels, field-diplomacy projects are being developed. Recently, the United Nations

Volunteers started projects to support the peace process in several conflict

areas in the world. Their project in Burundi endeavors to promote peace at a

community level through grassroots confidence building measures aimed at enabling

the emergence, return and social reintegration of persons in hiding internally

displaced people and refugees. Part of the project's efforts will be to shift

the dynamic of inter-group relationships from animosity and confrontation to

mutual esteem and cooperation. Training in conflict resolution will support

the efforts of community leaders for reconciliation, and lay a basis for a national

capacity to detect, preempt and defuse future tensions and latent conflict situations.

Peace education and promotion of respect for human rights will also be required.

The project will also help in building up a fabric of local and international

NGO support for the peace process. It will promote peace building efforts and

humanitarian relief simultaneously, and it will also practically help in advancing

the agenda towards sustainable social recovery and human development. To further

the cooperation between all these scattered peace services in the field, Elise

Boulding organised in May 1994 in Stensnäs (Sweden) a mini-seminar to prepare

the way for the establishment of a 'Global Alliance of Peace Services' (GAPS).

Although, to a great extent, inspired by and using techniques and methods of

Track II peace-making, field-diplomacy distinguishes itself in several ways.

First, field diplomacy requires a credible presence in the field. One has to be in the field to help to transform the conflict effectively. A credible presence in the field is needed to build a trust bank or a network of people who can rely on each other. This is necessary to get a better insight into the concerns of the people, the conflict dynamics, and for taking timely measures to prevent destructive action.

Second, a serious engagement is necessary. As the adoption of a child cannot be for a week or a couple of months, it is a long-term commitment. Facilitating a reconciliation process could be depicted as a long and difficult journey or expedition.

Third, field diplomacy favors a multi-level approach of the conflict. The actors in the conflict could be located at three different levels: the top leadership, the middle level leaders and the representatives of the people at the local level. A sustainable peace needs the support of the people. Since they have a major stake in peace, they should be stake holders in the peace-making, peace-keeping and peace- building process.

Fourth, field diplomats believe that peace and the peace process cannot be prescribed from the outside. They favor the elicitive approach. One of the most important tasks of field diplomacy is to identify the peace making potential in the field. The role of field diplomats is to catalyze and facilitate the peace process. Any peace process should be seen as a learning experience for all the people concerned.

Fifth, field diplomats have a broad time perspective, both forward and backward. A sustainable peace demands not only a mutually satisfying resolution of a specific conflict but also a reconciliation of the past and a constructive engagement towards the future.

Sixth, field diplomacy focuses also attention to the deeper layers of the conflict -- the deep conflict. Most peace efforts focus on the upper layers. They are concerned with international and national peace conferences and peace agreements signed with pomp. A lasting peace needs to take care of the deeper layers of the conflict: the psychological wounds; the mental walls; and the emotional and spiritual levels. The latter refers to the transformation of despair in hope; distrust in trust; hatred in love. Our understanding of these soft dimensions is very limited. We have a long way to go.

Seventh, another characteristic of field diplomacy is the recognition of the complex interdependence of apparently different conflicts. Field diplomats do not only reject the artificial distinction between internal and external conflicts, but pay attention to the interdependence of different conflicts in space and time. Many Third World conflicts have not only roots within the country or the region, but also in the North. The conflicts in Rwanda and Burundi cannot be uprooted if not enough attention is paid to the behavior of Belgium or France in the past and present. There is also some fieldwork to be done here and now.

Eighth, field diplomats stress the importance of a more 'integrative approach of the peace process.

Several factors endow religions and religious organizations with a great and under-utilized potential for constructive conflict management.

First, more than two thirds of the world population belongs to a religion. In 1992, 29.2% of the religious constituency was Christian; 17.9% Muslim; 13% Hindu; 5.7% Buddhist/Shintoist; 0.7% Confucianism/Taoist. Together, all those religious organizations have a huge infrastructure with a communication network reaching to all corners of the world. They have a great responsibility and leadership is expected from them.

Second, religious organizations have the capacity to mobilize people and to cultivate attitudes of forgiveness, conciliation. They can do a great deal to prevent dehumanization. They have the capacity to motivate and mobilize people for a more peaceful world. Religious and humanitarian values are one of the main roots of voluntarism in all countries: doing something for someone else without expecting to be paid for it. They are problem-solvers. They do not seek conflict. But when a need is seen, they want to do something about it. They are a force to be reckoned with (Hoekendijk, 1990).

Third, religious organizations can rely on a set of soft power sources to influence the peace process. Raven and Rubin (1983) developed a useful taxonomy for understanding the different bases of power. It asserts that six different sources of power exist for influencing another's behavior: reward, coercion, expertise, legitimacy, reference, and information.

Reward power is used when the influencer offers some positive benefits (of a tangible or intangible nature) in exchange for compliance. If reward power relies on the use of promises, coercive power relies on the language of threat. Expert power relies for its effectiveness on the influencers' ability to create the impression of being in possession of information or expertise that justifies a particular request. Legitimate power requires the influencer to persuade others on the basis of having the right to make a request. Referent power builds on the relationships that exist between the influencer and recipient. The influencer counts on the fact that the recipient, in some ways, values his or her relationship with the source of influence. Finally, informational power works because of the content of the information conveyed.

To mediate, religious organizations can rely on several sources of power. There could be the referent power that stems from the mediation position of a large and influential religious family. Closely related could be legitimate power or the claim to moral rectitude, the right to assert its views about the appropriateness and acceptability of behavior. Religious leaders could refer to their 'spiritual power' and speak in the name of God. Also important could be the informational power derived through non-governmental channels; groups like the Quakers could use expertise power on the basis of their reputation of fine mediators.

Fourth, religious organizations could also use hard sources of power. Some religious organizations have reward power, not only in terms of promising economic aid, but, for example, by granting personal audiences. Use could also be made of coercive power by mobilizing people to protest certain policies. Think of Bishop James McHugh, warning President Clinton of an electoral backlash for the administration's support of abortion rights at the United Nations population conference in Cairo. Integrative power, or power of 'love' (Boulding, 1990), is based on such relationships as respect, affection, love, community and identity.

Fifth, there is a growing need for non-governmental peace services. Non-governmental actors can fulfill tasks for which the traditional diplomacy is not well equipped. They would provide information not readily available to traditional diplomats; they could create an environment in which parties could meet without measuring their bargaining positions, without attracting charges of appeasement, without committing themselves, and without making it look as if they were seeking peaceful solutions at the expense of important interests. They could monitor the conflict dynamics, involve the people at all levels, and assess the legitimacy of peace proposals and agreements.

Sixth, most can make use of their transnational organization to provide peace services. Finally, there is the fact that religious organizations are in the field and could fulfill several of the above peace services.

Several weaknesses limit the impact of religious organizations in building a world safe from conflict. Several religious organizations are still perpetrators of different kinds of violence. In many of today's conflicts they remain primary or secondary actors or behave as passive bystanders.

Also inhibiting religious peace-making efforts is the fact that, as third parties, religious organizations tend to be reactive players. They seem to respond better to humanitarian relief efforts after a conflict has escalated than to potential violence. A third weakness is the lack of effective cooperation between religious organizations. Most of the peace making or peace-building efforts are uncoordinated. Finally, there is a need for more professional expertise in conflict analysis and management.

Religious organizations have a major impact on inter-communal and international conflicts. During the Cold War, religious as well as ethnic and nationalist conflicts were relatively neglected in the study of international relations and peace research. After the implosion of the communist block, the escalation of nationalist violence was a surprise. Some expect an escalation of religious conflicts as well. Despite an increase in the attention to the religious dimension of conflicts, it remains an under-researched field. There is no useful typology of religious conflicts; no serious study of the impact of religious organizations on conflict behavior; no comparative research of peace-making and peace-building efforts of different religious organizations.

The world cannot survive without a new global ethic, and religions play a major role, as parties in violent conflicts, as passive bystanders and as active peace-makers and peace-builders. Hans Küngs' thesis that there cannot be world peace without a religious peace is right. Representing two thirds of the world population, religions have a major responsibility in creating a constructive conflict culture. They will have to end conflicts fueled by religion, stop being passive bystanders and organize themselves to provide more effective peace services. Religions and religious organisations have an untapped and under-used integrative power potential. To assess this potential and to understand which factors enhance or inhibit joint peace ventures between the Christian religions, but also between the prophetic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), the Indian religions (Hinduism and Buddhism) and the Chinese wisdom religions, is an urgent research challenge.

Assefa, Hizkias. 1990. "Religion in the Sudan: Exacerbating conflict or facilitating reconciliation" Bulletin of Peace Proposals, Vol. 21 No. 3.

Bauwens, Werner and Luc Reychler, ed. 1994. The art of conflict prevention. London: Brassey's.

Boulding, Kenneth. 1990. Three faces of power. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Burton, John. 1984, Global Conflicts, the Domestic Sources of International

Crisis. Maryland:

Wheatsheaf Books.

Ceadel, Martin. 1987. Thinking about peace and war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fein, Helen, ed. 1992. Genocide watch. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gantzel, Klaus, JürgenTorsten Schwinghammer, Jens Siegelberg. 1993. Kriege der Welt. Ein systematischer Register kriegerischen Konflikte 1985 bis 1992. Bonn: Stiftung Entwicklung und frieden.

Goldfarb, Jeffrey. 1989. Beyond Glasnost: The Post-Totalitarian Mind. Chicago: University of ChicagoPress

Hoekendijk, Liebje. 1990. "Cultural roots of voluntary action in different countries" Associations Transnationales, 6/1990.

Hunter, James Davison. 1991. Culture wars: the struggle to define America. New York: Basic Books.

Huntington, Samuel. 1993. The clash of Civilizations? New York: Foreign Affairs.

Küng, Hans, 1990. Mondiale verantwoordelijkheid. Averbode: Kok-Kampen Altioria.

Princen, Thomas, 1992. Intermediaries in international conflict. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Reychler, Luc, 1979. Patterns of diplomatic thinking. New York: Praeger publishers.

Sauer, Tom. 1992. The Mozambique peace Process, paper, John Hopkins University, Bologna Center 1992/1993.

Search for Common Ground. 1993. Report, Washington DC.

Shenk, Gerald. 1993. God with us? The roles of religion in conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Research Report of the Life and Peace Institute15 December 1993.

Stewart-Gambino, Hannah. 1994. Church and State in Latin America, in Current History, March 1994.

Weigel, George. 1991. "Religion and Peace: An argument complexified," The Washington Quarterly, Spring/1991.

Williamson, Roger. 1992. "Religious fundamentalism as a threat to peace: two studies" Life and Peace Studies, Oktober/1992.

Williamson, Roger. 1990. "Why religion still is a factor in armed conflict?" Bulletin of Peace Proposals, Vol.21, No. 3.